How to Develop a Clone Recipe

Ever wonder how to develop a clone recipe?

After a few goes at the local homebrew shop’s recipe bank, most of us start building our own recipes. And because we’re homebrewers it’s natural to want to recreate another brewery’s beer, both as homage and to avoid paying retail. Sometimes it’s easy to find a clone recipe, and other times the brewer’s lips are sealed. That reaction is a bit strange, as it’s highly unlikely that your rendition of a brewery’s beer will taste exactly like the original.

So why is that? If you use the same malt, hops, and yeast, there should be little variation in flavor. But there are a few key factors that affect the way your beer tastes; it all boils down to house character.

Many breweries capitalize on their house character, in various ways. Some will isolate, cultivate, and bank a genetic mutation of a common yeast strain that ferments the way they like it. For example, here in Oregon, Block 15 Brewing uses a “proprietary” strain that evolved from English ale yeast. Many breweries that brew wild and sour beers will harvest naturally occurring yeast and bacteria from the air or fresh fruit in order to incorporate the “terroir” of their location.

Location will also determine the quality of water used in the brew. Many breweries get around that by filtering and treating water prior to brewing in order to get consistent results. Without knowing the mineral content of the brewing water, it’s pretty hard to make a beer that tastes and feels the same as its commercial counterpart.

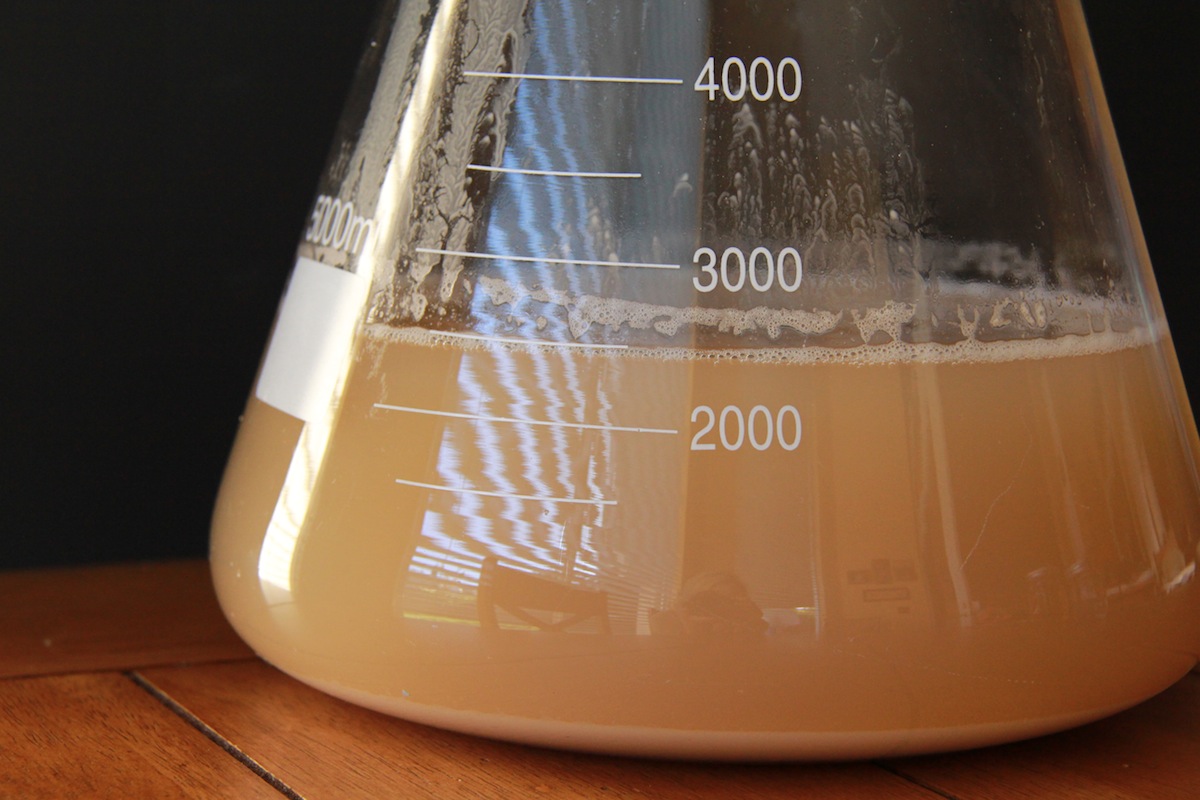

It may sound crazy, but the shape of your fermentor affects the flavor of your beer! The common tall, cone-bottomed fermentors found in most breweries are more favorable for brewing ‘cleaner’ tasting beer, as the greater gravitational force on the beer inside suppresses ester formation. For example, it can be harder to brew a hefeweizen in these fermentors without adjusting fermentation temperature and yeast pitch rate. Wider, flat-bottomed fermentors favor ester production; English and German ales are often “open fermented,” which is not to be confused with spontaneous fermentation. Instead of the standard sealed vessel with a blowoff tube (you would be surprised how much pressure a blowoff tube creates), the fermentor is open at the top (though it may be covered with a lid). Fermentation activity will generally keep contaminants at bay, and the lack of pressure will let the yeast produce their fruity glory at will. Just some more little details to keep you up at night trying to formulate the perfect recipe. Now it might really be rocket science!

I brewed an IPA last year that was a mash-up of two of my favorites: Breakside IPA and Deschutes Fresh Squeezed IPA. Deschutes lists all of the ingredients in its beers on its website, only without quantities; this is a great challenge for homebrewers. I also found the ingredients for Breakside IPA that came directly from the brewer, Ben Edmunds, on a homebrew forum. Again, without specific quantities. The stats are listed for each: abv, IBU, original gravity, yeast. Edmunds even gave notes on water treatment, which is rare. Here is my recipe, which I daresay turned out well; I can’t say whether it tasted like one or the other because it’s both! If you really love hop aroma, go ahead and dry-hop the beer with any of the finishing hops; 3-5 days at room temperature should work. And if you want to be really edgy, put an ounce into the fermenter just before the beer reaches terminal gravity; yeast can metabolize hop oils into different aromatic molecules! Links to online calculation resources are included at the end.

Cheers!

FreshSide IPA (Breakside IPA & Deschutes Fresh Squeezed Mashup)

Target Gravity: 1.062

IBU: ~70

Grain Bill:

Crisp Maris Otter – 90%

Weyermann Munich I – 5%

Great Western Crystal 15 – 3.5%

Great Western Crystal 40 – 1.5%

Adjust the water in your hot liquor tank. For example, to 15 gallons of Eugene tap water, I added 10g gypsum (CaSO4), 4g, Calcium Chloride, and 2g Epsom Salt (MgSO4) to give the following profile:

64ppm Ca / 5ppm Mg / 116ppm SO4 / 6ppm Na / 36ppm Cl / 17ppm HCO3

Mash in at 148F and let rest for 60-90 minutes, until conversion is complete. Vorlauf and sparge. While collecting your wort, add 1oz. Chinook hops to the kettle, then continue with the hop bill when the boil has begun:

60 min. – Columbus (CTZ) to 45 IBU

5 min. through flameout (in 10 gallons):

1 oz Chinook

2 oz Citra

2 oz Mosaic

2 oz Falconer’s Flight blend

(This big late addition of hops not only provides the rest of the IBUs wanted, but ensures a full Northwest hop aroma in the finished beer.)

Chill and rack to fermenter. Ferment in the mid to upper 60s on a clean American ale strain (Wyeast 1056, White Labs 001, Imperial Flagship). Should finish around 1.010. Enjoy!

Water chemistry adjustment calculator